ISLAMABAD — Pakistan’s credibility as a destination for foreign investment has suffered a devastating blow after Qatar’s Al Thani Group announced its withdrawal from the $2.09 billion Port Qasim Power Project — a decision that underscores the country’s deep institutional decay, financial dysfunction, and chronic inability to honor its commitments.

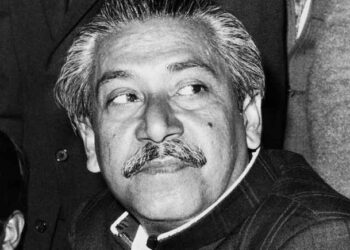

The collapse of what was once billed as a flagship energy partnership between Islamabad and Doha did not happen overnight. It began quietly in 2024, when Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jaber Al Thani, Qatar’s former prime minister, wrote directly to Pakistan’s leadership demanding $450 million in overdue payments. The letter went unanswered. Nearly a year later, with the debt still unpaid, Qatar finally walked away — an unmistakable vote of no confidence in a government that has turned delay and default into routine policy.

A Pattern of Broken Promises

The Port Qasim debacle has become a metaphor for Pakistan’s wider economic rot. Contracts, once backed by sovereign guarantees, now carry little weight. The Central Power Purchasing Agency owes nearly Rs 400 billion to independent power producers, while foreign corporations from Shell and TotalEnergies to Pfizer and Uber have shuttered operations, citing chronic payment delays and bureaucratic chaos.

“Pakistan has crossed the line from risky to uninvestable,” said one senior energy executive based in Dubai. “If even Qatar — a friendly Gulf ally — cannot collect its dues, what hope do others have?”

The Energy Paradox

At the heart of this implosion lies Pakistan’s circular debt — a structural quagmire that has strangled the power sector for more than a decade. By September 2025, it had ballooned to Rs 1.693 trillion, rising Rs 79 billion in just three months. Including the petroleum sector, the total surpasses Rs 5.7 trillion.

The irony is cruel. The country boasts a generation capacity of nearly 42,000 megawatts, almost double its national demand, yet Karachi and other cities remain plagued by daily blackouts. Billions are funneled into “capacity payments” to idle plants, many built under China’s CPEC framework, where investors are guaranteed dollar-indexed returns as high as 34 percent — even when no power is produced.

“These are acts of economic self-sabotage,” said a former official at Pakistan’s energy ministry. “We are paying for electricity we don’t use, borrowing to cover losses we created, and blaming everyone but ourselves.”

Mismanagement and Moral Bankruptcy

Pakistan’s leadership acknowledges the crisis but has done little to solve it. Former Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi admitted last year that power purchase agreements were signed by officials “who didn’t understand what they were negotiating.” The energy regulator, NEPRA, has long lacked the capacity to oversee such complex deals, leading to contracts that guarantee private profits while bleeding the state.

Foreign direct investment has collapsed by more than half, plunging 55 percent year-on-year to just $185 million by September 2025 — compared with India’s $81 billion in the same period. Even Bangladesh now attracts more inflows.

Once lauded for its cheap labor and strategic location, Pakistan has squandered its advantages through political meddling, corruption, and institutional paralysis. Transparency International ranks the country 133rd worldwide for corruption, while the World Bank places it 128th for governance quality.

A Breach of Faith

The Port Qasim project, backed by one of the world’s wealthiest royal families, now stands as an emblem of that failure — a multimillion-dollar facility facing shutdown simply because Pakistan’s government cannot pay its bills. Project management has warned that further non-payment would constitute a breach of the state’s sovereign guarantee, effectively declaring that the word of Pakistan’s government no longer carries value.

Islamabad has tried to patch the damage by arranging a Rs 1.275 trillion local financing package to reduce circular debt and renegotiating IPP contracts. But these measures resemble triage more than reform — temporary fixes for a system that has lost credibility both at home and abroad.

A Nation Running Out of Excuses

Qatar’s withdrawal signals something larger than a failed investment. It marks the unraveling of Pakistan’s reputation as a trustworthy economic partner. For decades, Gulf allies extended goodwill and capital to Islamabad despite instability and poor governance. That patience has now expired.

“When your friends stop believing you, it’s over,” said a senior Gulf banker familiar with the matter. “Pakistan has run out of excuses — and out of credit.”

As investors flee, energy shortages deepen, and debts mount, Pakistan faces an existential question: how long can a state survive when its promises — written, spoken, and sworn — no longer mean anything?

Source: