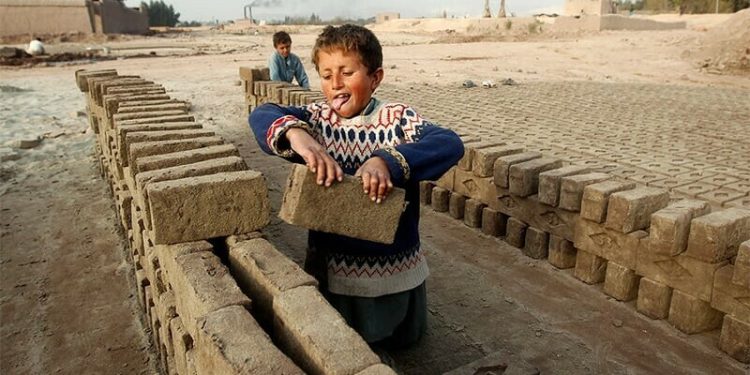

KARACHI, Pakistan: A new UNICEF-backed survey has exposed Pakistan’s continuing failure to protect its children, revealing that more than 1.6 million minors in Sindh province are trapped in child labor — with half of them working under dangerous and exploitative conditions.

Despite repeated promises and laws aimed at child welfare, the findings underscore Pakistan’s deep-rooted poverty, corruption, and government neglect that have allowed this human rights crisis to persist for decades.

According to Syed Muhammad Murtaza Ali Shah, Sindh’s Director General of Labor, the survey — conducted between July and August with technical assistance from UNICEF and the Bureau of Statistics — found that 10.3 percent of Sindh’s children aged 5 to 17 are engaged in labor. Of them, nearly 800,000 work in hazardous environments, risking their health and lives daily for survival.

The study paints a grim picture of the province’s rural heartlands. In Qambar Shahdadkot, child labor rates reached a shocking 30.8 percent, followed by Tharparkar (29 percent) and Tando Muhammad Khan (20.3 percent). Even the country’s financial hub, Karachi, recorded 2.38 percent — a reminder that the crisis is nationwide.

Education appears to be another casualty of Pakistan’s failing system. Only 40.6 percent of working children attend school, compared to 70.5 percent of those not forced into labor — revealing how economic desperation robs millions of their right to education and a better future.

Shah admitted that provincial authorities are trying to “update laws” and “conduct raids” to curb illegal child labor. However, critics say such measures are largely symbolic in a country where poverty, weak governance, and social inequality continue to push children into the workforce.

While the Sindh government claims progress — noting a 50 percent reduction in child labor since 1996 — experts argue that the figures still expose Pakistan’s systemic moral and administrative collapse.

“The government can’t boast about progress when nearly two million children are toiling in fields, workshops, and factories instead of classrooms,” said one Karachi-based human rights activist. “This isn’t poverty alone — it’s a national failure.”