By Staff Correspondent

For decades, Pakistan has promoted itself as a guardian of religious pluralism, highlighting restored gurdwaras, interfaith initiatives and high-profile Sikh pilgrimages from India. But rights advocates and minority representatives say these gestures obscure a harsher reality: the steady disappearance of Sikh communities and the state’s increasingly strategic management of religious identity.

At the time of Partition in 1947, territories that now comprise Pakistan were home to an estimated 5.9 million non-Muslims. Today, officially registered minorities represent only a small fraction of the population. Hindus account for roughly 2.1 percent, Christians 1.3 percent, Ahmadis 0.09 percent, while Sikhs, Parsis and others make up even smaller shares. Rights groups contend that these figures themselves understate the decline, citing migration, under-reporting and fear of identification.

Among the most sharply affected communities are Sikhs. Activists estimate that Pakistan’s Sikh population has fallen from around 40,000 in the early 2000s to roughly 8,000 today. They attribute the decline to discrimination, economic marginalization, intimidation and conversion-related pressure.

A Pilgrimage That Raised Questions

Concerns resurfaced in November following the disappearance of an Indian Sikh pilgrim, Sarabjit Kaur, during a religious visit to Pakistan. She later appeared before a magistrate in Sheikhupura, submitting a sworn statement that she had converted to Islam and married a Pakistani citizen, Naseer Hussain, of her own free will.

Pakistani media outlets portrayed the episode as a personal decision and an example of religious harmony. Sikh organizations and rights observers, however, urged caution. According to individuals familiar with the case, Ms. Kaur had been in contact with Mr. Hussain for nearly nine years. Rights advocates note that prolonged emotional dependence and religious persuasion are recurring features in cases later presented as voluntary conversions.

What has drawn particular scrutiny is the response of Pakistani authorities. Despite apparent violations of visa conditions, Ms. Kaur was not deported. Instead, her case was routed through the Lahore High Court via a petition related to visa irregularities. Legal observers say the focus on conversion and marriage transformed what could have been a routine immigration matter into a politically charged narrative, one that played prominently in domestic media.

Critics argue that the episode allowed the symbolism of an Indian Sikh woman “embracing Islam” to circulate widely while delaying legal resolution.

A Broader Pattern

Human rights organizations say the case fits a broader pattern. Across Pakistan, minority girls—and in some cases married women—have been reported abducted, forcibly converted to Islam and married. Once conversion certificates and marriage documents are presented before a magistrate, families often find legal remedies effectively closed.

Men from minority communities face different vulnerabilities. Employment discrimination remains widespread, while Pakistan’s blasphemy laws—among the strictest in the world—are frequently invoked against non-Muslims. Accusations alone can lead to prolonged detention, mob violence or death, regardless of eventual acquittal.

Curated Minority Leadership

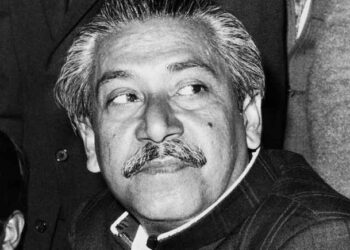

Analysts also point to the state’s management of minority representation. One frequently cited figure is Gopal Singh Chawla, a controversial Sikh leader who for years maintained visibility within official and religious circles. Diaspora observers allege he functioned as a conduit for state-approved narratives on Sikh affairs. He is now reportedly under house arrest, his public role abruptly curtailed.

In his place, the government has elevated Ramesh Singh Arora, currently Punjab’s Minister for Minority Affairs. While presented as a reformist voice, rights advocates argue his rise reflects alignment with official positions rather than grassroots support, reinforcing claims that minority leadership is curated rather than independently empowered.

Allegations of Instrumentalizing Faith

Rights activists have raised even more troubling allegations, including claims that a Christian man from Faisalabad, Yusuf Masih, was coerced into converting to Sikhism as part of an intelligence operation aimed at infiltrating Sikh pilgrim groups. According to these accounts, when he failed to meet expectations, he was allegedly handed over to counterterrorism authorities, held in illegal custody and subjected to severe abuse. Independent verification has proven difficult amid restricted access and fear of retaliation.

A Structural Crisis

Taken together, these accounts point to a systemic problem, rights groups say. Pakistan’s minorities are not only shrinking in number but are increasingly treated as instruments of ideology, diplomacy and internal security narratives. Conversions are celebrated when they align with state messaging; legal processes appear selectively enforced when symbolism outweighs rule of law.

As Pakistan continues to project an international image of religious tolerance, observers argue that the experiences of its remaining minority communities tell a more troubling story—one that raises questions about whether pluralism is being practiced, or merely performed.