The events of January 5, 2026, have injected new volatility into an already fraught national debate around Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). By intertwining a campus anniversary with a recent Supreme Court decision, the university has once again found itself at the centre of a legal and political storm that extends far beyond its walls.

On that night, the usually quiet corridors of JNU echoed with slogans that have come to define a decade of institutional tension. What began as a vigil marking six years since the 2020 campus violence soon transformed into a protest against the Supreme Court’s refusal to grant bail to former students Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam. The convergence of memory, protest and judicial outcome reignited a persistent question in Indian academia: can a university retain its standing as a premier research institution while also becoming a platform for rhetoric the state brands as “anti-national”?

The Long Shadow of 2020 — and Now 2026

For the Jawaharlal Nehru University Students’ Union (JNUSU), the “A Night of Resistance” vigil was a legitimate expression of democratic dissent. Student leaders maintain that the 2020 attack, when masked assailants assaulted students as police allegedly failed to intervene, remains an unresolved trauma.

The university administration and the Delhi Police, however, offer a sharply different interpretation. They cite slogans directed at the Prime Minister and the Home Minister as evidence of “intentional misconduct” and a “wilful disrespect for constitutional institutions.” Acting swiftly, the administration has described the campus as a potential “laboratory of hate” and sought FIRs against student leaders, reflecting a broader national sentiment that publicly funded institutions must demonstrate loyalty to the republic.

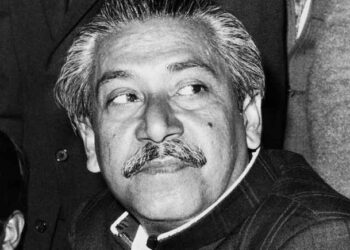

The Sharjeel Imam Question

The decision to foreground Sharjeel Imam’s case during the vigil has proven especially divisive. Supporters portray Imam as a victim of an excessively harsh legal regime, while critics recall his remarks about “cutting off” the Northeast from India.

Recent observations by the Supreme Court — that Imam and Khalid occupy a “qualitatively different footing” from other accused in the Delhi riots case — have further sharpened the debate. For some, this judicial stance strengthens arguments that JNU has strayed from its academic mission. They contend that solidarity with individuals whom the court sees as prima facie central to a conspiracy against the state signals a profound institutional drift.

Taxpayer Money and the Limits of Protest

The controversy has also acquired an economic dimension. With the Delhi Police filing a Non-Cognizable Report under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita for “public mischief,” questions are being raised about the continued use of taxpayer funds to support what is perceived as a culture of subversion.

Defenders of the university counter that JNU’s contributions — reflected in its NIRF rankings and its “Deprivation Points” system that brings students from rural and marginalised backgrounds into higher education — are too significant to dismiss. They warn that criminalising protest risks stifling intellectual vitality and undermining the very purpose of a university.

A Campus, and a Country, Divided

JNU today stands deeply divided. One side views it as a “Tukde-Tukde” ecosystem that must be dismantled in the interests of national security; the other regards it as a crucial bastion of free thought, essential to the health of Indian democracy.

The developments of January 2026 suggest that space for compromise is rapidly shrinking. If JNU cannot reconcile its tradition of critical inquiry with the expectations of a state increasingly intolerant of dissent, calls to “shut it down” may no longer remain rhetorical — and could soon find expression in policy itself.