By Mir Yar Baloch

The proposal to include Pakistan on any international body charged with advancing peace in Gaza is not merely ironic—it risks reducing diplomacy to farce. A state long accused of nurturing militant proxies and tolerating extremist networks now finds itself presented as a moral stakeholder in conflict resolution, a contradiction too glaring to ignore.

Pakistan’s global reputation has for decades been clouded by allegations of duplicity in the so-called “war on terror.” The discovery of Osama bin Laden living openly in Abbottabad, a garrison city that hosts Pakistan’s premier military academy, remains one of the most damaging episodes in modern intelligence history. It exposed, at best, staggering incompetence, and at worst, a willful blindness sustained while Islamabad received billions in Western aid.

The country’s powerful Inter-Services Intelligence agency (ISI) has repeatedly been accused—by governments, intelligence agencies, and analysts—of supporting militant organisations such as Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed, groups linked to major attacks including the 2008 Mumbai atrocities and subsequent violence in Kashmir. These actors are often described not as rogue elements but as strategic assets in Pakistan’s regional policy playbook.

Even Pakistan’s own leaders have acknowledged the scale of the problem. In 2019, then-Prime Minister Imran Khan publicly admitted that tens of thousands of armed militants were operating within the country—an extraordinary confession from a sitting head of government.

The moral contradictions deepen when viewed through history. In 1971, the Pakistani military’s Operation Searchlight in what was then East Pakistan resulted in mass civilian deaths during the war that led to the creation of Bangladesh—an episode widely regarded as one of the worst humanitarian catastrophes of the twentieth century. The victims were overwhelmingly Muslim.

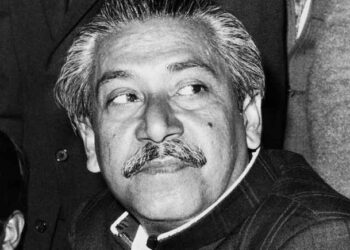

Nor does Pakistan’s record sit comfortably with its frequent claims of solidarity with Palestinians. During Jordan’s Black September in 1970, Pakistani military officers served with King Hussein’s forces during a brutal crackdown on Palestinian factions—an operation that left tens of thousands dead and entire refugee camps destroyed. One of those officers, General Zia-ul-Haq, later ruled Pakistan as a military dictator and remains a celebrated figure in the country’s official narrative.

In the present day, Pakistan’s internal security operations in Balochistan and the Pashtun belt are routinely criticised by human rights organisations. Reports from groups such as Human Rights Watch and assessments by the U.S. State Department have documented enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, torture, and systematic repression of ethnic and religious minorities, including Shias, Ahmadis, Hindus, and Sikhs.

Criticism has not been confined to foreign observers. Senior religious and political figures within Pakistan have openly questioned what they describe as selective and performative counter-terrorism campaigns that disproportionately impact civilians while leaving militant infrastructure intact.

Against this backdrop, Pakistan’s inclusion in any “peace board” addressing Gaza appears less like a gesture toward reconciliation and more like a triumph of geopolitical convenience over principle. It raises uncomfortable questions about what standards, if any, govern international peace initiatives.

Even former U.S. President Donald Trump—hardly a habitual critic of security partners—accused Pakistan in 2018 of “lies and deceit,” pointing to its receipt of vast American aid while allegedly harbouring extremist leaders. His administration briefly suspended security assistance in response.

Peace processes depend not only on dialogue but on credibility. Elevating a state persistently accused of exporting instability while repressing its own population risks eroding the very moral authority such initiatives require.

If the international community is serious about peace—whether in Gaza or elsewhere—it must stop rewarding duplicity and start confronting it.